The urgent need for a socially just and ecologically sustainable approach to water governance became evident early on in the history of Both ENDS. In the 1990s, Both ENDS was supporting people’s movements against huge, destructive hydroelectric dam projects, like the Narmada dam, in India. While campaigning against such top-down approaches to water management, Both ENDS and partners realised that the widely accepted concept of ‘Integrated Water Resources Management’ (IWRM) was not delivering on its promises of inclusiveness and sustainability.

As a response to the controversial Narmada Sardar Sarovar dam and irrigation projects in neighbouring states, local NGO’s Gangotree and Econet prepared a comprehensive river basin development plan for the Banas river, integrating dozens of old and modern techniques for local water management into one ingenious scheme. The variety of methods and solutions tested made the approach relevant for other areas too.

At the same time, partner organisations around the globe were similarly engaged in successful, people-centered water management initiatives. They were working in other river basins and embedded in different societal and environmental contexts. Yet all of the initiatives used a bottom-up approach that put local communities’ realities, knowledge and aspirations at the core of water management.

Cotahuasi Valley where AEDES worked on river basin management. Peru, around 2003

Continuous Contour Trenching, a way of soil and water conservation on slopes. Gogalwadi, India, around 2004

The evidence collected by all of these initiatives challenged the “classic” concept of IWRM and demonstrated the importance of a people-centred approach to managing water and the environment.

Guiding principles for the negotiated approach

In 2005 Both ENDS, Gomukh Environmental Trust for Sustainable Development in India, and seven partner organisations (from Bolivia, Peru, Vietnam-Cambodja, Thailand, India, South Africa en Bangladesh) working on river basin management joined forces to document their strategies and experiences. Based on these different cases, the groups presented the concept of ‘the Negotiated Approach’ to IWRM. In 2011 Both ENDS and Gomukh followed up with the booklet ‘Involving Communities: A Guide to the Negotiated Approach in Integrated Water Resources Management’, which described the ten guiding principles behind the approach.

‘The booklet is blue, but it was not meant to be a blueprint,’ quips Melvin van der Veen, who specialises in inclusive water governance at Both ENDS. ‘An important element of the negotiated approach is that it is flexible, taking socio-political and cultural factors into account.’ Other key elements that distinguish the Negotiated Approach from Integrated Water Resources Management more generally are prioritisation of self-motivated local action and empowerment of local communities to assert their rights to water. ‘The negotiation must be meaningful’, says van der Veen. ‘It’s not enough that local communities are seated at the table. They must be equipped with negotiation skills and have the power to assert their rights.’ At the same time, those with traditionally more powerful positions shouldn’t be allowed to dominate the process. It only works when all stakeholders can engage equally.

Local irrigators meeting, Nan river, thailand, 2003

Community map of Se San river in Cambodia, 2003

Both ENDS now prefers to call the approach ‘Inclusive Water Governance’. Van der Veen explains: ‘It was not immediately clear to people what we meant by the term Negotiated Approach. Negotiation may sound as if communities are giving something away; the new term shows precisely what is crucial: inclusiveness. We haven’t changed anything about the approach itself, but we learned how to communicate about it more effectively.’ Both ENDS has worked to inspire donors and other organisations to support inclusive water governance, spreading the message alongside partners in key forums like the annual World Water Week conference in Stockholm.

Strategically adapting to a changing context

What has changed in the ten years since the blue booklet was published? Although in most cases the technical aspects of water governance are still dominant above the socio-political aspects, the importance of an inclusive approach to water management is more widely acknowledged. Van der Veen points to some important developments in the right direction, like in Kenya where the role for communities in natural resource management has been formalised in Water Resource Use Associations for each sub-catchment in the country’s six major river basins.

There is also more attention in the water sector to the importance of women’s rights to water and their role in water management. A gender-responsive approach is already part and parcel in the work of Both ENDS’s partner organisations, like Ecoton in Indonesia, where women leaders are organising and advocating for clean water, and Uttaran in Bangladesh, which is supporting a new generation of women leaders to be part of gender-balanced water committees in the country’s southwest.

The Dutch link to Both ENDS’s work on water has become more prominent in recent years. Dutch businesses and the Dutch government increasingly present themselves as experts in climate adaptation for coastal and delta areas and play an active role in water projects around the world, including coastal development projects, like those for Jakarta and Manila. In 2016, when partners in Indonesia signalled serious flaws in the consultation process and social and environmental threats posed by the Jakarta plan, Both ENDS echoed their concerns to key (Dutch) actors involved in the projects, and facilitated dialogues between partners and different stakeholders.

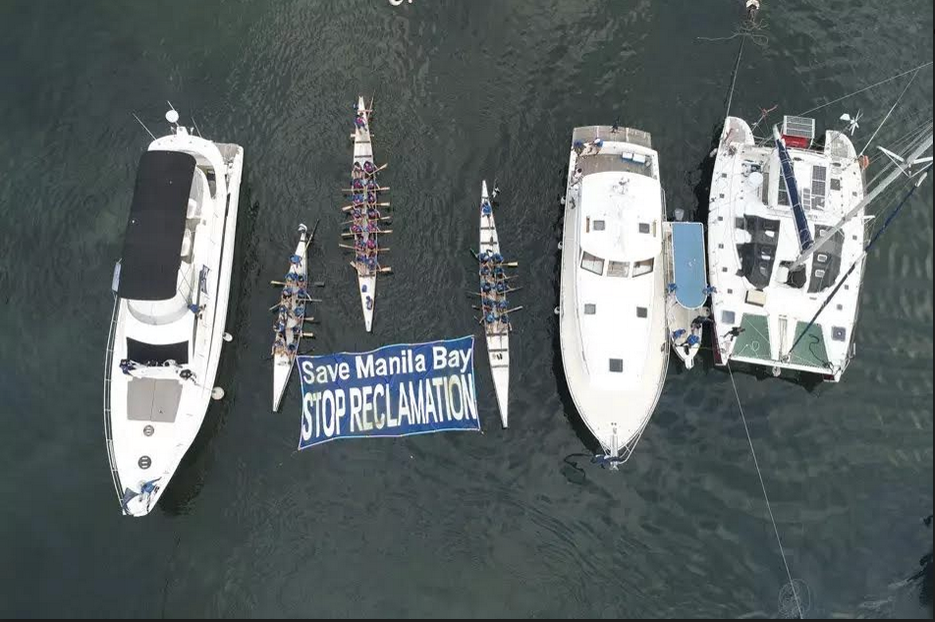

More recently, Both ENDS has been collaborating with partners in the Philippines. Joint research has shown that the master planning process for Manila Bay and proposed projects do not show regard for human rights and hardly consider local communities’ needs, concerns and existing initiatives. ‘It was not developed with the meaningful participation of the people who are currently most affected and most vulnerable to future climate change impacts. We’re translating these findings into advocacy activities. Local partner organisations are also planning to develop a holistic People’s Plan by and for the people living in Manila Bay and its related ecosystem, as an alternative proposal for the protection and development of Manila Bay,’ says van der Veen.

Fishing communities protest against the Jakarta Bay plans which include a large seawall and land reclamation

In Manila Bay, coastal communities fear to lose their livelihood strategies when the large-scale land reclamation plans are being realized

Both ENDS and partners have been moving with the tide, adapting their strategies to promote inclusive water governance as climate change accelerates. Typhoons, hurricanes, flooding, droughts, rising sea levels – all are increasingly threatening the existence of communities and landscapes around the world. Coasts are eroding. Sea levels are rising. Lagoons are disappearing. Climate refugees are putting pressure on cities that are often already struggling with rapid urbanisation, while those who stay behind are exposed in an increasingly vulnerable situation.

Looking for new allies

‘The urgency and complexity of the problem pushes us to look for new partnerships,’ says Van der Veen. ‘We won’t and don’t need to compromise our principles. Yet we need to look for new allies that are complementary to achieving the change we envision.’ To that end, Both ENDS has stepped up engagement in the Netherlands Water Partnership (NWP), a network of some 180 Dutch companies, NGOs, knowledge institutes and governmental organisations in the water sector. In 2018, Daniëlle Hirsch, Director of Both ENDS, became chair of the NWP’s NGO Platform and consequently also a member of the NWP Board. Having learned from cases like Jakarta and Manila, members of the NWP are increasingly engaging in conversations with Both ENDS.

Furthermore, Both ENDS together with the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the RVO (Netherlands Enterprise Agency, a government entity that supports Dutch businesses) is looking how water projects can be financed in such a way that they strengthen the position of local water users. ‘The issue is not just about water,’ says Van Der Veen. ‘It’s about giving people a voice – decision-making power – over their environment.’

Community workshop in the Athi river basin, Kenya, 2019

Indonesian women measure the water quality, 2018