‘You can only solve the great issues in the world together with the people directly involved in them’

Sjef Langeveld in 2020

Sjef Langeveld was the director of Both ENDS from the end of 1999 to the end of May 2008. He looks back on an eventful decade, in which Both ENDS slowly came of age. Start from the strengths that are already there, that was and is Sjef Langeveld’s motto: ‘I took the gold in the organisation as my starting point.’

Sjef, you came straight into Both ENDS as director, and were also new at that time in the sector of international cooperation. What did you know about Both ENDS and what appealed to you about the job?

That’s right, I had a background as landscape architect, urban and rural planner, ecologist and researcher within the Netherlands. I had always had the ambition and motivation to work internationally. I didn’t become involved in international projects until I went to work at Wageningen University.

I didn’t know Both ENDS, but when I heard that they were looking for a director, I contacted them and they asked me to come in to talk about it. Then I knew immediately that the job fitted me like a glove.

It was what I really wanted to do. I wanted to work on issues relating to water and land for the people – farmers, citizens and local residents – who use them every day. That was exactly what Both ENDS did, and still does. You can only solve the great issues in the world together with the people directly involved in them. You have to take their rights and their energy as your starting point.

What kind of organisation was Both ENDS when you started as director? What did you need to start working on straight off?

I wanted Both ENDS to be recognised as an organisation that mattered, that legitimation was very important to me. That appreciation was already there, of course. I saw that as soon as I walked in the door. I call that ‘the gold of Both ENDS’, but there was no certainty. So that’s where I started: securing the basic funding with the help of Cordaid, paying people a decent salary, and generating recognition from the outside world.

When were asked in 2002 whether we wanted to take over Inzet, the international organisation of the Dutch Labour Party (PvdA), that was confirmation for me that we were on the right track. Both ENDS was appreciated for its work and that brought financial security. We obtained more funding from the Ministries of Environment and Foreign Affairs.

Besides that recognition for Both ENDS within the Netherlands, what was for you the most interesting aspect of the organisation’s work in your period as director? Where was that ‘gold’?

I found the Drynet programme very interesting. We started it back then, first in the Sahel and then expanding it to other regions. Is that still going?

Yes, it’s now a CSO network, with the secretariat in South Africa.

So that was a success, excellent! It was a fundamental response to degradation: stopping degradation by reforestation, using the land differently, starting with local residents themselves. I thought the Negotiated Approach was very exciting, too, but that was already in place. Drynet was really new.

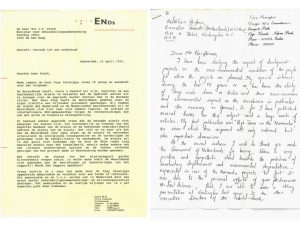

What I also found very interesting was forest garden products. That was a joint programme with Cordaid that enabled the products of ‘forest dwellers’ to be marketed in Europe. And the Joke Waller-Hunter Initiative, set up with Joke’s estate, is also very special. I never met her myself but she was very important to Both ENDS from the beginning.

After Joke’s death, the executor of her will asked me to take responsibility for her estate. She had left instructions for the money to be devoted to develop international leadership among young people working for NGOs. I immediately told Irene Dankelman [who was a board member at that time, ed.] and, when I got back to the office, she was there with all our colleagues. I told everyone about Joke’s wishes, and they were all very moved. For a moment, it seemd like Joke was there is the room with us. It was very special.

Langeveld pauses, lost in though. Then:

If you look at the varied patchwork of Both ENDS’ work, you wonder where the consistency comes from. But if you have a patchwork, you have all the stitches that hold it together. Those stitches are our basic values. Human rights and the environment, linked, joined together.

But if you ask me what the most important parts of our work were from that period… I want you to mention, besides Drynet, the Negotiated Approach.

What is so special about the Negotiated Approach?

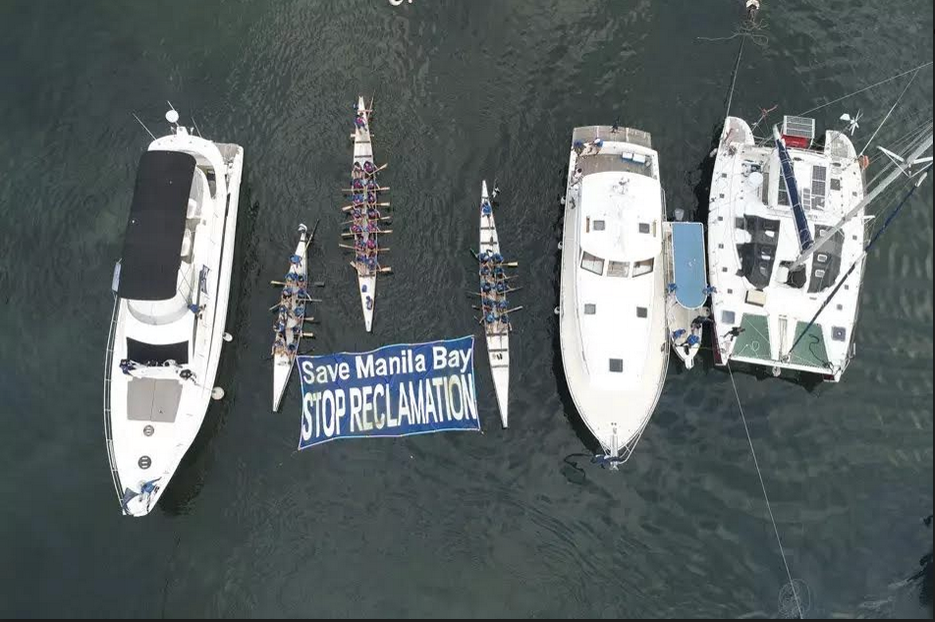

It’s about the value of water, the involvement of local residents in how that water is managed, and the guarantee that they are in control. But that is extremely difficult! It is their water and their concern and their resource but it is distributed, with dams and irrigation, to the benefit of those in power.

We had a project with seven river basins around the world, and everywhere they were trying to give people control over their water. After everything I had experienced in the Netherlands, with how water was managed and the changes in the Dutch water sector, the mergers of the small water authorities into a few very large ones, I found that very strange. With all my water experience in the Netherlands, I couldn’t understand why we were increasing the distance between residents and their water here, while in the seven regions in the project the movement was in the opposite direction.

To conclude the project, all the partners came to the Netherlands and I arranged a visit to the water authority and dyke warden at Alblasserwaard. When our bus arrived at the water authority offices, the dyke warden opened the doors and told us that the offices were empty. The authority had been incorporated into a larger one. The water authority that I wanted to show the visitors, how it was set up, with an entrance for the local residents and so on – it was all gone!

On the way back, Vijay Paranjpye [from India, one of the founders of the Negotiated Approach, ed.] said ‘We have made a big mistake in this project. We should have included the Rhine basin in it. The management has been handed over to a large bureaucratic body. You could have learned a lot from us!’ He had a good point there.

Working together with the people who are directly involved: that’s how you approached your work at Both ENDS, but it also applies to Markdal, where you live and have been involved in for a number of years now. I see a close similarity there to the Negotiated Approach.

Yes, there is, isn’t there? And that’s very necessary in this country. Degradation is just as bad here as everywhere else. The soil is over-fertilised and depleted, biodiversity has decreased alarmingly. That overloading of the original system is apparent all around the world. In the Markdal, we want to create a natural environment, allow the river to flow freely and lush vegetation to return, so that biodiversity increases again.

Sjef Langeveld with the project manager of the municipality in Markdal. Still from video by OMOOC, 2017

You have seen solutions all around the world for degraded catchment basins and to combat soil degradation. Did you learn lessons at Both ENDS that you can now apply in Markdal?

Yes, the solution lies with those who are responsible for the land, who use it and extract water from it. At Markdal, we’ve made a deal with the provincial authorities: let us, as residents and land-owners, strengthen the natural environment ourselves and get the river flowing freely again, within the limits set by your administrative aims. We discovered that local farmers wanted the same. Then you’ll find a solution together on how to do that. There are no standard ways of approaching it. It’s a matter of trial and error, and the Negotiated Approach is a good guiding framework.

The strategy you choose can then be repeated over and again: people trust each other, give each other space. But there can still be problems, such as language. The farmers are tired of the way they are spoken to and about. The provincial authorities say ‘bottom up’ instead of ‘from within’, and an ‘area-based process’ rather than ‘a society-based process’. If you speak of ‘bottom up’, that means that the farmers and residents are at the bottom of the ladder. And in our work, society is the base, we start from the original value that that area has. From within.

You still follow Both ENDS closely. Where do you feel our legitimacy lies? Where is our gold these days?

That you show solidarity, that you provide a strong helping hand for others that need it. Standing shoulder to shoulder is important. We have the advantage of a good social context here. That gives us a responsibility to show solidarity with people in other parts of the world who are grappling with the same challenges that we face. Then you’ll see that they do the same for us. That reciprocity is at the core of the fight for human rights and for the environment.